Piano Tuner in Inverclyde, Renfrewshire, Glasgow, the west of Scotland and beyond.

Tel: 07714959806

Clementi Sonata in Bb 1st Mvt.mp3

Birdcage Pianos

This piano has what's often called the Birdcage action. The correct name is the Overdamper action (or overdamped action). The name "birdcage" comes from the vertical damper wires at the front, fancifully imagined as the bars of a birdcage.

Another photo of the same overdamper action:

Another overdamper action:

In Overdamper actions the felt pads - dampers - which stop the strings from sounding when you let the keys up, are above the level of the hammers, sitting nearer to the ends of the strings.

All modern upright pianos have Underdamper actions, with the dampers below the hammers.

The photo below shows an Overdamper action from the hammer side, with the dampers above the line of the hammers. (Dampers don't extend into the high treble on any piano as the tones there are of short duration).

Overdamper actions were popular in budget-level British pianos around the end of the19th century. They were often fitted to straight strung - also called parallel strung - pianos, where the bass strings do not run across diagonally over the treble strings.

Here's an illustration from a 1920s Catalogue of the Sames Piano Company. This is the cheapest model in the catalogue, straight strung and with overdamper action:

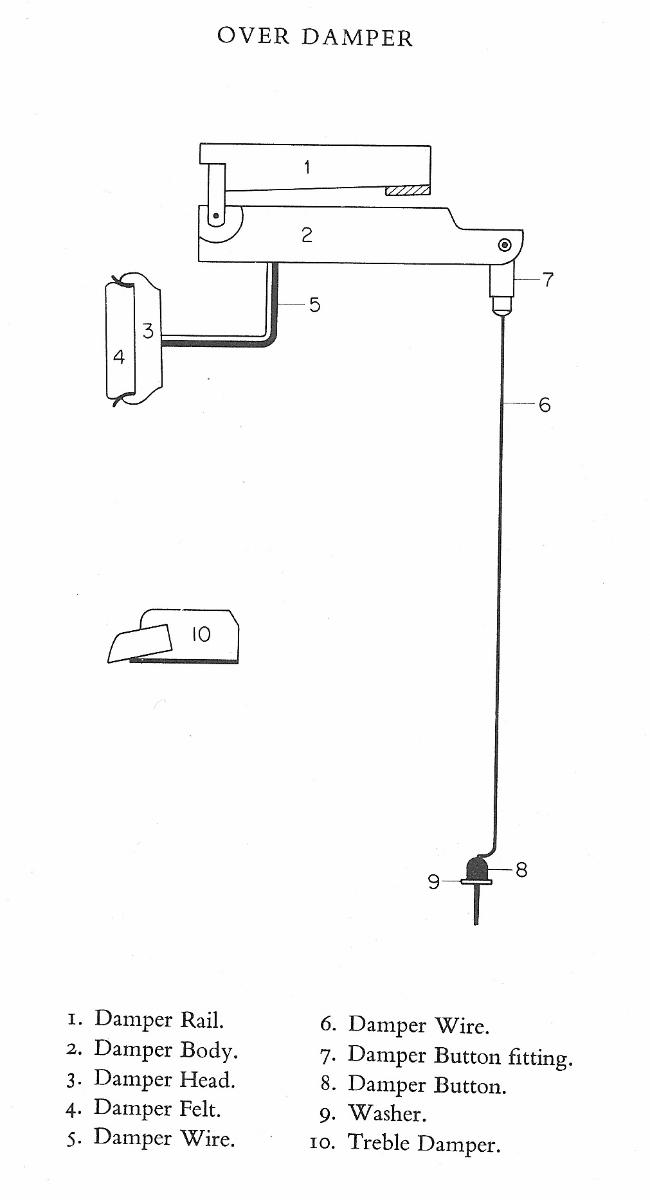

A line drawing of the overdamper mechanism for a single note. It's shown without the rest of the action. The hammer (not shown) which strikes the string, sits just below the level of the damper.

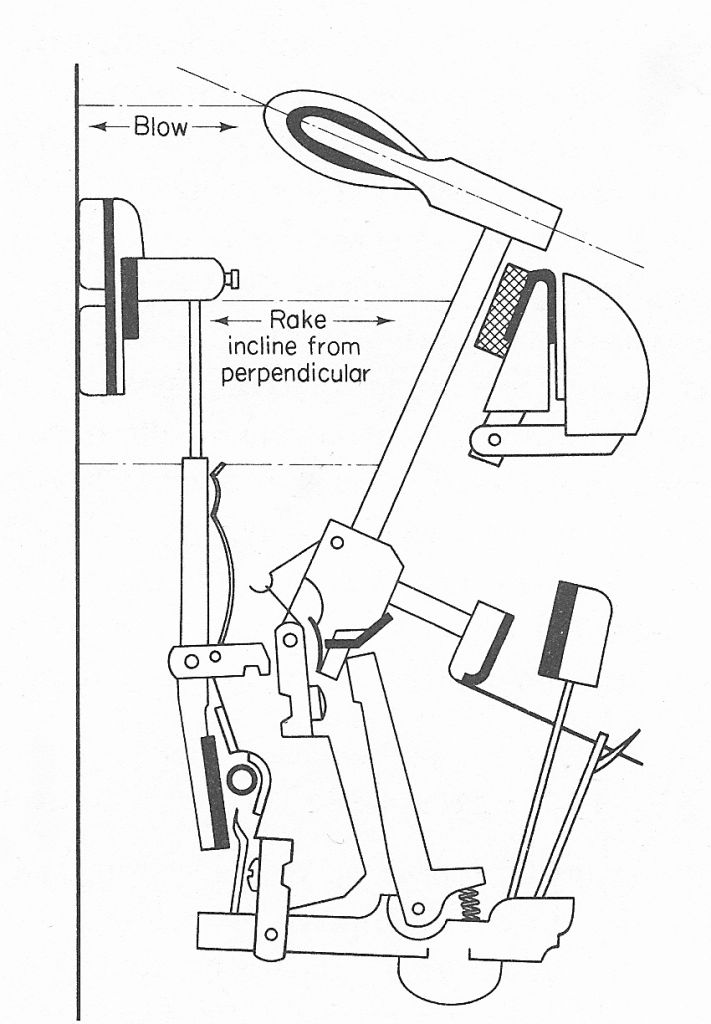

Compare with a modern upright action, with the damper below the level of the hammer. In that position it works more efficiently to stop the string from sounding. It's operated by a spring, which pushes the damper felt against the string. In the overdamper, only gravity keeps the damper against the string.

Birdcage actions tended to be fitted to the cheaper, straight-strung pianos. Perhaps for some reason they were slightly cheaper to manufacture.

In the late 1800s a thriving "cottage industry" of small piano workshops developed in England, making cheap and cheerful instruments to suit the budget of 'lower middle class' families, who by that time had the means and the desire to own a parlour piano. Scores of thousands of entry-level pianos were churned out by such workshops, cheaply made, to be affordable.

(There was a kind of upright piano around since the 1850s called the Cottage Piano - see the bottom of the Technical Info 1 page. That's not what I mean here by "cottage industry"; I'm using that term in its general sense).

In that era, beautiful hardwood veneers and the skilled labour to work with them were cheap. A result of this was that many of these late 1800s Birdcage pianos looked much better than they actually were. Look at the inside of the lid of this small 1800s Birdcage piano, for example:

Isn't that exquisite? Even on the inside of the lid, seldom seen.

Here is the whole piano. After 130 years the casework can be expected to look a little tired, but even so, you can see that it was pretty:

As time went on finishes became less ornate. Here's a photo of one of the later Birdcage pianos, typical of the size and style produced in the 1940s.

With the top and bottom doors and the action removed, the parallel stringing is visible (sometimes called 'straight-strung').

A similar example. Photographs of these pianos by gracious permission of the owners:

Top panel off, showing the overdamper action:

This piano illustrates the phenomenon of "badging", which has always happened in the piano manufacturing industry, and still does. The name on the fall (keyboard lid) is not necessarily that of the factory which made the piano. This piano said Crane & Sons, an old English make, and the nameplate inside bears the Crane name:

But the letter K in front of the serial number shows that the piano was made in the Kemble factory:

This serial number dates the year of manufacture to 1941, and Bill Kibby of www.pianohistory.info confirms that Kemble made pianos for Crane at that time.

Here is a close view of the little motif on the top panel, rather Art Deco in style. You may have noticed that the other piano of this type above, also had such a motif in the centre.

Although by the late 1930s, straight strung overdamper pianos were apparently being phased out in English manufacturing, Bill Kibby has pointed out out that they didn't entirely cease production until the mid 1950s. It seems likely that these were made using pre-war leftover stocks of these actions. Piano actions are made by separate specialist companies, and Herrburger Brooks were the main UK action maker for many years.

Kemble, incidentally, were the last English piano factory. They ceased production in October 2009, effectively ending 200 years of English piano manufacturing. There is still some artisan piano making going on, but not on a factory scale.

Here's another late 1930s birdcage piano. It looks very similar to the two above:

Like the piano above it, this one too has the Crane name on it.

And like the Crane above, a look inside quickly reveals a Kemble serial number:

However, unlike the two Kemble pianos in the pictures above, this one doesn't have an Art Deco motif on the top door, and, ta-dahhh! it is an OVERSTRUNG birdcage.

Here it is with the action out. Photos thanks to kind permission of the owner.

And just to show that Kemble did sometimes use their own name on birdcage pianos, here's another little 1941 upright in the same style as the badged Crane, but bearing Kemble's own name:

The internal nameplate is very much in the style of the Crane & Sons model shown earlier on this page:

And here is the serial number (sorry about the quality of these photos, taken with my phone):

Another English overstung birdcage, from a slightly earlier period than the Kemble models above; a bigger, heavier instrument:

This is a really old birdcage piano where the damper rail partly obscures the bottom row of tuning pins. This piano can never have been properly tuned in its life, until I filed grooves in the damper rail to let the tuning lever get access. As it was made, you had to use the tuning lever to lever the rail down while simultaneously tuning and "setting" the pins; an impossible task.

It's an infuriating aspect of many of the smaller overdamper pianos, that part of the bottom row of tuning pins doesn't quite clear the top of the overdamper rail and this makes it very difficult to seat the tuning lever properly on those tuning pins. There is really no excuse for this; it's just bad design, with only cost-cutting having prevented a solution.

German Birdcage Pianos

Overdamper pianos were also made in Germany. There, it wasn't a bargain-basement thing: Bluthner notably made some huge and powerful pianos with overdamper actions - there used to be three of them in my immediate area. Ibach were another German maker who had overdamper actions in some fine pianos.

However, the German makers did not persevere as long with that type of action as British manufacturers did. They seem to have dropped those designs some time around the First World War. I don't think overdamper actions were ever used by the USA piano industry.

Overdamper actions do not "damp" the strings (stop them from sounding after you take your fingers off the keys) quite as effectively as underdamper actions, partly because the dampers are close to the ends of the strings where there is less string movement. The damping becomes even less efficient with age.

Here is a Youtube clip from Roberts Pianos in Oxford, showing one of the fine old Bluthner overdamper pianos, and comparing it to another that has had a new underdamper action installed - a very labour-intensive and expensive job.

I came across this German piano with both underdampers and a half-set of overdampers:

This piano with its half-set of additional overdampers makes it easy to see how the overdamper mechanism works (I should have dusted the hammer rail before taking the photo!):

They were certainly determined that the bass strings of that piano would damp! That's an awful lot of damper felt, both above and below the hammers. The top rail isn't really curved, it's an artefact of the wide angle of the camera lens:

Spring & Loop Birdcage Action

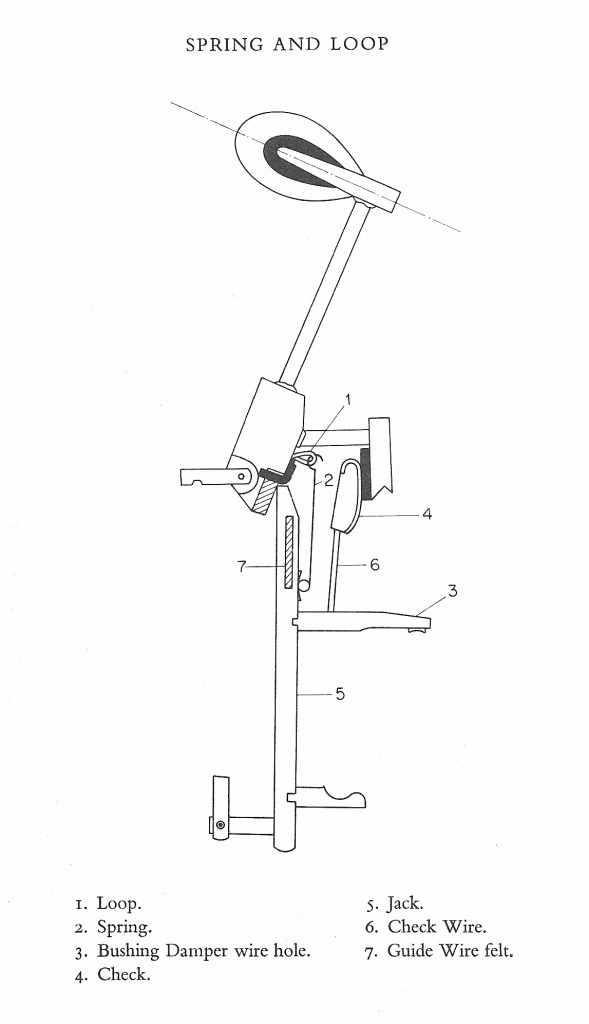

An early variant of the Birdcage action was the Spring & Loop type. The top two photographs on this page show an Overdamper action of the Spring & Loop type. These actions were commonly used early on in the cheaper upright pianos. Later Birdcage actions had Bridle Tapes, more closely resembling modern Underdamper tape-check actions, and worked better. The geometry of Spring & Loop actions was inferior, and in my experience, they never feel responsive and, I think, did not even when new..

This line drawing shows a Spring & Loop mechanism for one note. It's shown without the overdamper, so you have to imagine the overdamper drawing above, in place here, with the damper above the hammer.

The first two birdcage (or overdamper) action photos, at the top of this page, are of the Spring & Loop type action. Later overdamper actions were of the Tape Check type. The Tape Check, or Bridle Tape, is still what is used in modern underdamper actions to tie action parts together and assist hammer rebound. The third and fourth photos on this page are of a Tape Check overdamper action, as is this photo:

'Modernised' Birdcage Pianos

In Britain in the 1950s a fashion developed for 'modernising' the casework of older pianos to make them look more contemporary. Ornate front panels were replaced with plain fronts without candle sconces. Straight legs were replaced with curved ones. Top lids were shortened so that they did not overhang, and rounded-corner mouldings were fitted.

The following photos show a typical example:

The refinished top panel does not quite match the keyboard lid (called the Fall).

The top panel has been replaced with a plainer look, lacking inset panels and candle sconces. The finish on the Fall is original.

Typically, such 'modernising' involved shortening the top lid, which would originally overhang the top of the piano and have a wooden moulding round it (like the Sames model in the catalogue above). The sides of the modernised piano would then have a rounded moulding fitted, as below:

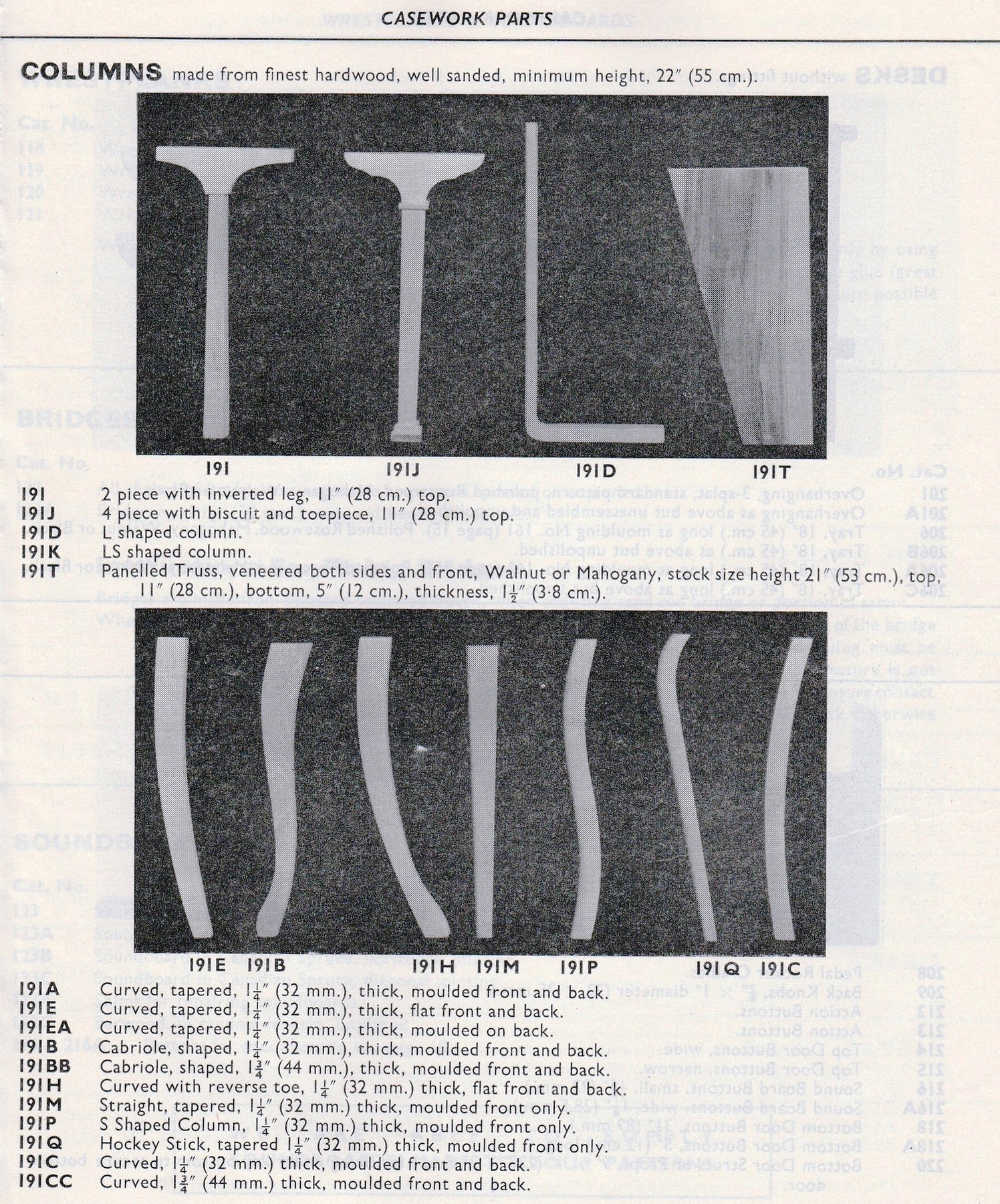

These curved legs are also typical of such refurbishments. An early 1960s catalogue of UK piano trade supplier Fletcher & Newman is full of case parts like these replacement curved legs, for modernising old pianos.

All these renovations were purely cosmetic. They did nothing to improve the operation of the piano as a musical instrument or to deal with sixty years of wear to the action parts. But it did make the piano look younger.

One client was very surprised when all this was explained to her. She insisted that the piano had been sold to her parents as brand new in 1957, but it was quite clear that it was a "modernised" piano. A 1918 date stamped on the piano's birdcage action helped to convince her.

Here is a page from a 1959 supply house catalogue showing some of the case parts available to workshops then for "modernising" old pianos:

Should you buy a Birdcage piano?

What is the upshot of all this, as far as buying or owning a Birdcage piano is concerned? Broadly, the advice must be:

Don't buy one, and if you own one, don't expect that it can be improved.

The high-quality German Birdcage pianos are now too old to be candidates for major improvement, unless for the very best-quality ones and in a wealthy area where people will pay a premium price for such a restored piano.

The later UK Birdcage pianos, from the mid 1930s to the early 1950s may still be playable, but they were of budget quality, and not worth any great expenditure.

Worst of all are the late 19th century English cottage-industry Birdcage pianos, especially with the unresponsive Spring & Loop action. They were cheap to begin with, and are now around 130 years old - about twice the normal working lifespan of a piano. Action parts along with other parts of the piano become fragile with age, and there's little scope to make such old brittle Birdcage actions serviceable.

Line drawings on this page are from Piano Action Repairs & Maintenance K.T. Kennedy, Kay & Ward, London 1979, out of print.